What is a Gasket?

A gasket is meant to form a mechanical seal that fills the space between two or more mating surfaces. Its goal is to prevent leakage from, or into, the joined objects while under compression.

Gaskets allow for less-than-perfect mating surfaces on machine parts. They can fill irregularities and increase the likelihood of sealability — especially in high-pressure applications and flanges that have a high differential temperature range (cyclic flanges).

There are many different types of gaskets used in the oil and gas (petrochemical) industry and other heavy industry. They include both standard ANSI/ASME pipe flanges (an example is ASME B16.5 flanges) and gaskets used in heat exchangers.

What Nachos Can Teach You About Proper Gasket Assembly

What most people don’t know is that the gasket stress is what we care about the most! Not the bolt load.

We use this analogy when training people: “What is the purpose of the chip in chips and queso? It’s the vehicle that gets the queso to the mouth.”

That is the purpose of the bolt: To be the vehicle to gets the gasket stress correct.

What are the Most Common Types of Gaskets Used in Oil and Gas?

Here are the 8 types of gaskets you will see the most often:

1. Envelope Gasket (Double Jacketed Gaskets)

Envelope Gaskets can be either double jacketed gaskets, or they can have PTFE (some call it Teflon but that is a trademarked name) on the outside of a stainless steel metal core. However, they don’t have a lot of compression or recovery, and do not hold up to radial sheer (slipping of the flanges on the gasket during high-temperature fluctuations).

2. Flat Metal Gaskets

These gaskets usually have a stainless steel core without any filler material, and are used in low criticality applications. They also don’t have a lot of compressibility or recovery.

3. Non-Asbestos Sheet Material Gaskets

Non-asbestos sheet material is typically found with full-face flanges and have elastomeric properties, although they can be just graphite gaskets in few cases. One can have high chemical resistance sheet gaskets such as a PTFE/ePTFE gasket that has great compressibility and a little bit of recovery if you don’t overstress them.

Normally, these gaskets are used with low pressure and low temperature, but they can be also put in put in flanges where chemical resistance is needed. Most gasket manufacturers stock a wide range of elastomeric, non-elastomeric, PTFE/ePTFE, graphite gaskets, and compressed sheet material in both sheets and rolls.

4. Ring Type Joint

Ring Type Joint gaskets are also called RTJ gasket, ring gasket or ring joint gaskets. They come in oval or octagonal shapes, which can be used in API 6A applications.

RTJ gaskets were traditionally found in high pressure and high-temperature applications, as sheet material elastomers can not hold up in those types of applications. But today RTJ gaskets are being phased out of high pressure and high-temperature applications, as spiral wound gaskets with inner rings are now the preferred gasket.

However, if you are using ring type joint gaskets, know that they are typically made of a soft stainless steel gasket material, and should be replaced after every use due to the plastic deformation that it sees in the flange. If you don’t replace it, you are jeopardizing the sealability of the gasket.

5. Kammprofile Gasket

You’ll also see Kammprofile spelled “camprofile gasket,” and they are sometimes called grooved metal gaskets. These types of gaskets are commonly found in heat exchangers in the oil and gas industry.

They are much more reliable than jacketed gaskets (double jacketed gaskets). Kammprofile gaskets are typically made of a stainless steel metal core with a flexible graphite filler material.

The area (a.k.a cross-section) of the gasket can be easily changed to achieve good gasket stress while withstanding a high bolt load. Kammprofile gaskets are also really great for radial sheer which is seen when the flanges slip on each other (really the flexible graphite filler) during flange expansion and contraction (due to temperature).

This gasket material is a solid metal gasket, and the metal core can be made of stainless steel or other exotic materials so that it can be put in high pressure and high-temperature flanges.

To learn more about Kammprofile Gaskets, click here.

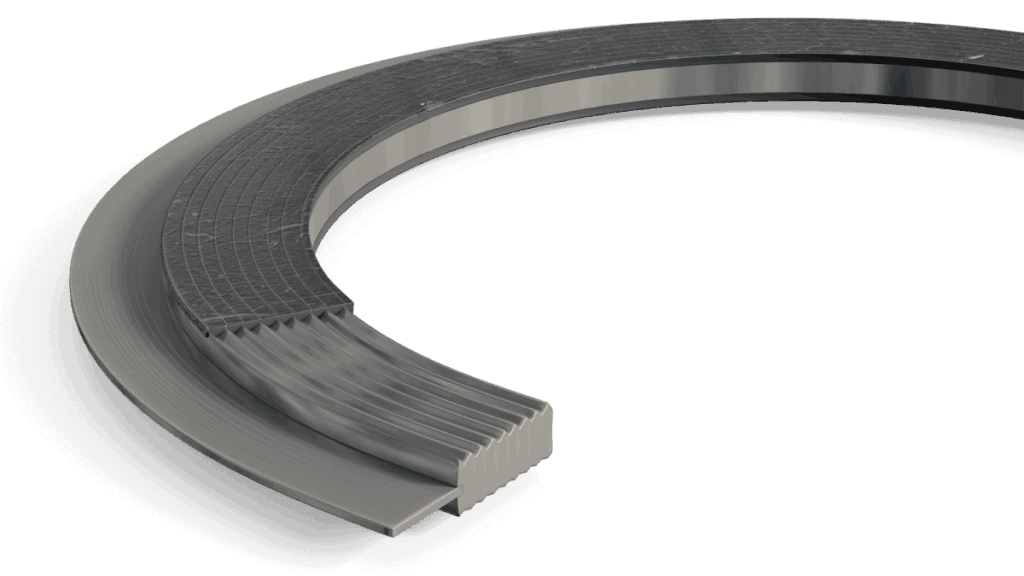

6. Spiral Wound Gaskets WITH an Inner Ring

These types of gaskets are the best metal gaskets for all pressure ratings of pipe flanges, especially ASME B16.5 flanges.

I would argue that they are also great for heat exchangers due to their sealability tolerances with imperfections in flanges, and because they can be made for high pressure and high-temperature applications.

These spiral wound gaskets have a stainless steel inner ring, a carbon steel outer ring, and the metal core is made of stainless steel windings. The filler material is typically flexible graphite, but you can also have an elastomeric filler material such as PTFE if chemical resistance is needed.

Spiral wound gaskets are more also flexible than Kammprofile gaskets so they tend to also have more compressibility and recovery, but they are harder to place in a flange at larger diameters so it is advisable to move to Kammprofile gaskets.

To learn more about Spiral Wound Gaskets, click here.

7. Spiral Wound Gaskets WITHOUT an Inner Ring

These types of gaskets should not be used in typical pipe flanges, and especially not in high-pressure rated pipe flanges (such as 600 pounds or greater).

The reason: Spiral wound gaskets without inner rings can buckle under high gasket stress, such as what you’ll see when there is a lot of bolt area and little gasket area.

There are instances when a spiral wound gasket without a stainless steel inner ring or carbon steel outer ring can be used for groove flanges such as male/female flanges, but we will typically see that they will compress enough to not allow for recovery.

8. Corrugated Metal Gaskets

These gasket types can be made to have a minimum of 0.5″ cross-section and have been used to change gasket area. They are better than metal jacketed gaskets for heat exchangers, but should not be used in standard piping flange gaskets.

How to Identify a Gasket: A Color-Coded Chart

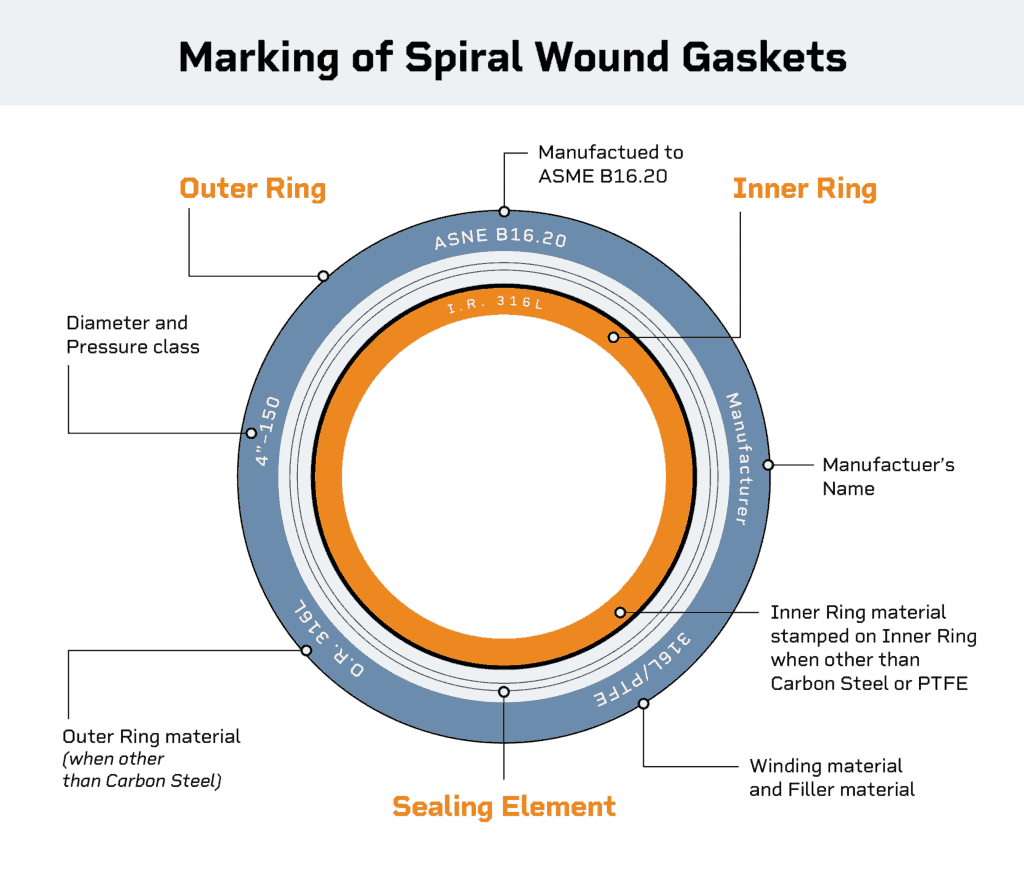

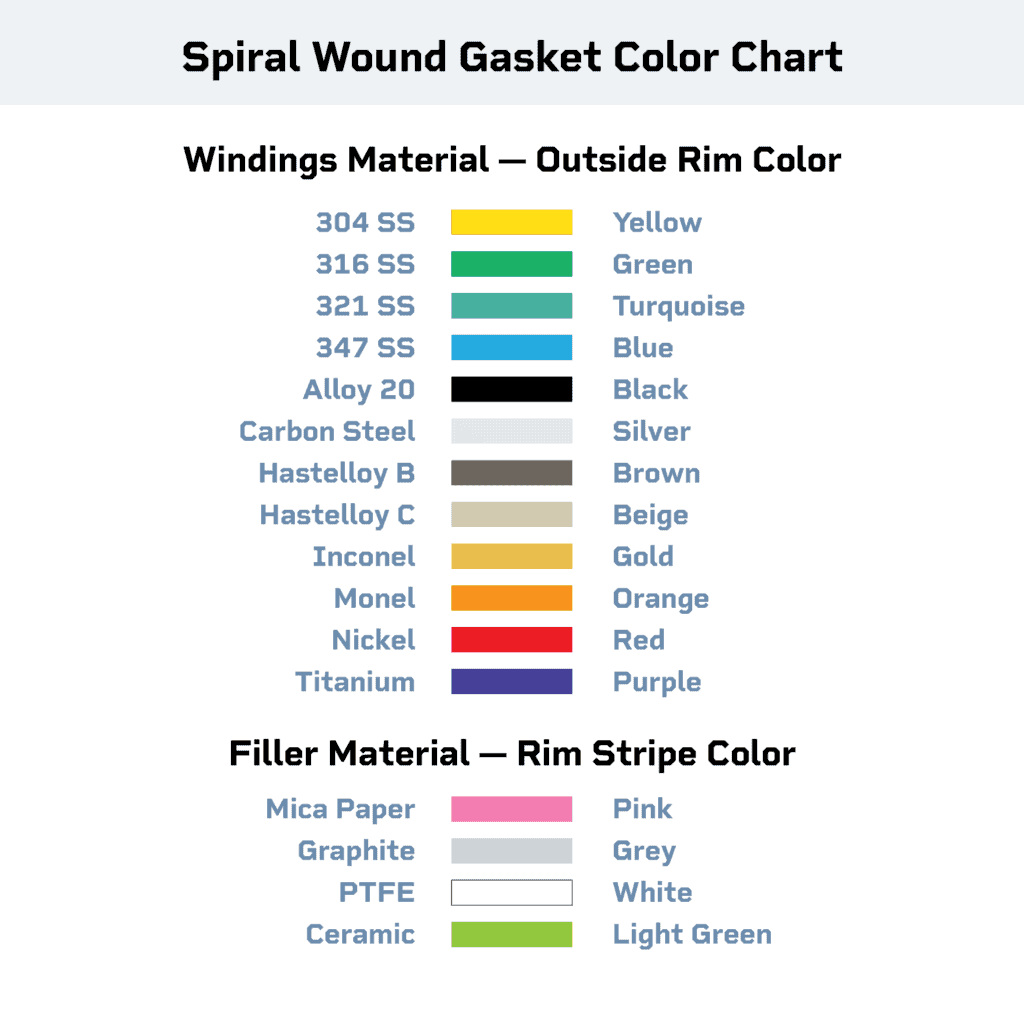

Most piping flange gaskets in the oil and gas industry today are spiral wound gaskets made of stainless steel for the metal core material with either PTFE or graphite filler material. ASME B16.20 offers a Color Coding Chart that is part of the standard for inspection purposes.

The color coating on the outer ring (which is typically carbon steel) is painted on the outside of the ring so that an inspector can identify the windings material.

Typically 316 stainless steel is used as the standard in petrochemical applications, as it is better for high-temperature applications. While 304 stainless steel could be used, most End Users in the petrochemical industry err on the conservative side for the 316 stainless steel which has a green color on the carbon steel outer ring.

The most common filler material is flexible graphite, and that is indicated by the grey stripe on the green outer ring.

The ASME B16.20 color chart above indicates what the gaskets are made of. NOTE: there is no marking for gaskets that do not have a stainless steel inner ring, so it is prudent that ALL spiral wound gaskets have an inner ring.

RELATED:

A Deep Dive Into Spiral Wound Gaskets

PTFE Coated Studs: Do They Work?

Join Industry Leaders!

Subscribe to Hex Technology today and we’ll give you $700 in bolting courses, FREE. Your path to a safer, more reliable, more profitable site starts here.